Victim or Villain: The sad story of Ike Ibeabuchi, the ‘President’ who went to jail

By Nnamdi Okosieme

He came from a clan established by a warrior.

His hometown, Isuochi, is one of the three autonomous communities making up Umunneochi( known officially as Nneochi), a Local Government Area in Abia State in Nigeria.

Legend has it that Ochi, a famed warrior and wrestler had settled in Nkwoagu, the centre of present day, Isuochi after wandering for a while in search of what one historian, described as “a healthy, stone-less and wind swept area for wrestling and other forms of sport”.

Ochi would later bear a son who in turn sired two sons, Ezi and Ihite. The two sons between them had nine sons, which today make up the nine villages of Isuochi.

In the footsteps of ancestor

Like his progenitor, Ochi, Ikemefula Charles Ibeabuchi, the boxer born in Okigwe(then part of East Central State in Nigeria but now part of Imo State), who would later come to be known around the world as Ike Ibeabuchi, the “President”, in 1993, left Nigeria for the United States of America.

His journey to America was facilitated by his mother, Patricia Ibeabuchi, who was a registered nurse in Dallas, United States.

As a teenager, Ike’s desire had been to pursue a career in the military. He had worked towards getting admitted into the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) where he had hoped to train to become a soldier.

That dream had been aborted by a twist of fate. In 1990, he had watched as James Buster Douglas destroyed Mike Tyson in 1990 in a world title boxing match. That fight left him thoroughly fascinated with boxing and jettisoning his plan to become a soldier he had turned to boxing as a means of livelihood.

Joining the amateur ranks in Nigeria, he had outclassed and defeated a field of boxers, which included Duncan Dokiwari, bronze medallist for Nigeria at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games and later, profession boxer in the United States, who he beat twice.

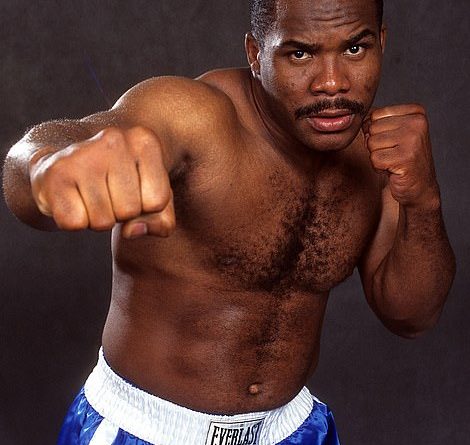

At 6 feet, 2 inches and with well-toned muscles, Ike was an intimidating hulk of man, a specimen of supreme athletic fitness. In Dallas where he lived with his mother, Ike chalked up victories in the amateur ranks, winning the Golden Gloves in the Dallas and Texas State tournaments in the heavyweight category in 1994.

That same year after pitching tent up with Curtis Coke, a former world champion in the Welterweight category as his trainer, Ike turned professional and on October 13, 1994, one year after he landed in America, the 21 year old boxer who had dreamed of becoming a soldier back home in Nigeria, won his first professional boxing match. His victim was Ismael Garcia who he knocked out in the second round.

Slugging into record books

The victory over Garcia opened a new vista for the young boxer, who quickly snagged 15 straight victories. By 1997, Ike had become a boxer of renown and boxing pundits believed he was credible contender for the heavyweight title.

His strength, stamina, speed and hard punching, had become noted around the boxing world and many suspected it would not be long before he became a world champion. That opportunity came on June 7, 1997 when he faced David Tua for the World Boxing Council (WBC) International Heavyweight title at the Arco Arena in Sacramento, California.

Despite Ibeabuchi’s impressive run, which stood at 17-0(17 wins, no losses with 15 of those victories coming via knockouts), he was dwarfed by Tua, a hard-hitting Samoan touted to be the next Mike Tyson. And it was not for nothing that Tua was highly regarded. Over a four-year period, he had amassed an impressive 27-0 record comprising 27 victories and no losses. Of the 27 victories, 23 were knockouts with 11 coming in round one.

And so on June 7, 1997, the boxing world held its breath as two of finest fighters around squared off at the Acro Arena in Sacramento, California. Ibeabuchi, the underdog, and Tua, the favourite put their past accomplishments aside, and blazed away in a flurry of punches that had their audience transfixed. For men their size ( Ibeabuchi stood at 6”2 and weighed 236 pounds and Tua at 5”10, weighed 226), the two fighters were remarkably fleet-footed. They went at each other with a pace and ferocity not seen among heavyweight boxers in recent times. They fought with an urgency that underscored their determination to rule the heavyweight division.

Writing about the fight, author and renowned boxing writer, Luke G. Williams, who writes for the Boxing Monthly, said:

“It’s fame owes nothing to the tangible laurels that the victor earned…Instead it owes its legendary status to its breathlessly relentless pace and beautiful brutality; a brutality reflected by a remarkable and oft-quoted statistic – of all the heavyweight fights analysed since 1985 by CompuBox, Ibeabuchi-Tua featured more punches thrown than any other heavyweight contest.”

Indeed, it was a fight to remember. With a whopping 1,730 punches thrown by Ibeabuchi and Tua in twelve rounds, it surpassed that of any fight with the closest being the 1591 punches thrown in fourteen rounds by boxing greats, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, in the epic “Thriller in Manilla” showdown in 1974.

Of the 1730 punches thrown, Ibeabuchi accounted for 975 at an astonishing 81.25 per round. In the end, Ibeabuchi won the fight by unanimous decision.

Unleashing his demons

The victory over Tua cemented Ibeabuchi’s status as a fighter of substance, In his own eyes, he was not only a heavyweight champion, he was the “President”, a title that been bestowed on him by adoring fans. He revelled in that moniker and it was said that he even took it too seriously.

“There were times when he thought he was really a president. He would get into these mental states where he insisted on people calling him ‘The President’. It was his alter ago, where ‘I am The President,’ not of the United States, but maybe president of the world,” Lou DiBella, boxing promoter and former HBO Sports executive once said of his attitude.

With this attitude, it was inevitable that he would get into trouble.

Months after his duel with Tua, Ibeabuchi kidnapped the old son of a former girlfriend and rammed his vehicle into a concrete pillar along the Interstate 35 north of Austin, Texas.

According to the boy’s family, the injury from the crash had incapacitated the 15 year-old and he would not be able to walk in a normal way with his legs. The court held that Ibeabuchi was attempting suicide. He was then sentenced to jail for 120 days for falsely imprisoning the abducted boy. He also paid $500,000 in civic settlement.

The abduction of the boy wasn’t the end of Ibeabuchi’s foibles. His promoter, the late Cedric Kushner once recounted an incident involving Ibeabuchi. Kushner said they were at a restaurant in New York for a meeting to work out a three-fight deal with HBO for the boxer. He said that in the middle of the meal, Ibeabuchi flipped and wielded a knife:

“We were having a fine meal at a nice restaurant and mid-course, Ike picked up a big carving knife, slammed it into the table and screamed ‘They knew it! They knew it! The belts belong to me! Why don’t they just give them back?’ That was a peculiar experience said. That wasn’t the type of conduct I expected to romance the guy from HBO. He (Ibeabuchi) was like a Viking,” Kushner said.

Getting his groove back

The abduction incident and other misdemeanour took their toll on Ibeabuchi and he went a full 13 months without activity in the ring.

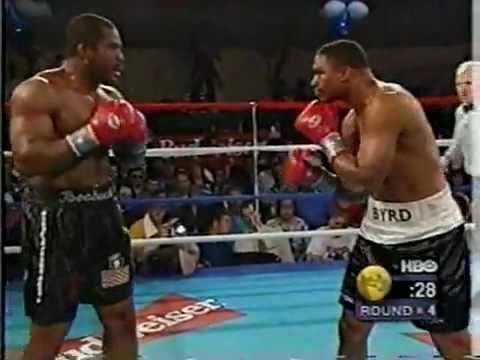

Despite these setbacks he was able to bounce back and secure ring victories against Tim Ray and Everton Davis before pulling off a spectacular victory against Chris Byrd in March 1999 at the Emerald Queen Casino, Tacoma, Washington. Coming into the fight, Byrd boasted a 26-0 record.

As was the case in the fight against Tua, there were doubts whether Ibeabuchi could take down Byrd, 1992 Olympic silver medallist. As the fight began, the two fighters engaged in a tit for tat, jabbing and retreating from each other.

After four rounds, they stood toe to toe. In the fight round however, Ibeabuchi, beginning with a solid left hook to Byrd’s chin, floored his opponent with a combination of devastating punches. Byrd rose valiantly to his feet but soon found himself cornered at the ropes by another flurry of punches prompting the referee to end the fight to save the boxer( who would later go on to become a world champion) further punishment.

The meltdown

The first fight against Byrd was Ibeabuchi’s last. From that point, his life took a tragic turn and promising career, which probably would have secured him a place in the pantheon of boxing greats collapsed against the contradictions of a volatile personality.

The journey to infamy began in July 1999, four months after his victory over Byrd. On that fateful day, Ibeabuchi, a guest at the Mirage Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, had called a local escort service to have a lady sent to his room. The company responded by sending a 21 year-old to him.

As the story goes, the young lady upon arrival told Ibeabuchi that she was there only going to strip for him and nothing else. The lady later told the police that Ibeabuchi had tried to rape her in the closet when she asked that she be paid up front for her service.

Ibeabuchi would later barricade himself in the bathroom and refused to open the door until the police shot pepper spray under the door.

The case against Ibeabuchi, who was initially released and placed under house arrest to enable train and fight pending his trial, was made worse by the reopening of a previous case of sexual assault against him by the District Attorney of Clark County. The incident had occurred eight months earlier at the Treasure Island Hotel and Casino.

However, after more similar allegations from Arizona came to light, he was remanded in custody.

From the texture of the allegations against him, Ibeabuchi was examined by medical experts who held him incompetent to stand trial on the ground that he suffered from bipolar disorder.

He was moved to a state-owned medical facility and with the permission of a judge, he was medicated by force. Eight months later, he was deemed competent to enter a plea. He entered an Alford plea. In United States law, particularly as it relates to the state of Arizona, the Alford plea, named after Henry Alford, a murder suspect in a Supreme Court case of North Carolina v. Alford (1970), “is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and asserts innocence. In entering an Alford plea, the defendant admits that the evidence presented by the prosecution would be likely to persuade a judge or jury to find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt”.

The judge sentenced Ibeabuchi to two to ten years for battery with intent to commit a crime (from which he was later paroled), and three to 20 years for attempted sexual assault, with the sentences to be served consecutively.

“Victim of conspiracy”

Ibeabuchi’s jailing broke the hearts of many boxing fans who had seen in him perhaps the next Mike Tyson or even George Foreman. They had hoped that his reign as heavyweight boxing champion will rekindle the glory of the sport fast disappearing in the face of dwindling talent.

None however, was more heartbroken than his mother, Patricia. For her, not only had the freedom of her son been taken from him, he had also been a victim of a conspiracy by boxing promoters who were out to ruin him. Determined to prove her son’s innocence.

Mrs Ibeabuchi immediately set up a website, www.helpikeibeabuchi.com(the website has since been taken down) were she made an impassioned plea for assistance to help free her son. In a detailed letter on the website titled, “Mother’s request for intervention”, she gave an account of what she said landed her son in jail.

She said in June 1999, three months after Ibeabuchi’s victory over Byrd, he learnt there was a boxing match in Las Vegas. From New Jersey where he had been attending a festival organised by his Nigerian kinsmen, he flew to Las Vegas to meet with officials of the HBO to discuss the possibility of a hammering out a contract. At this time, Ibeabuchi’s mother said her son’s contract with his promoter Kushner had expired.

“At this time Cedric was hounding Ike to renew his contract with him, Ike informed Cedric that he needed to shop around to have better understanding what his worth was and if he matches it, that he will continue with him. Cedric was not happy about this because he knew that he had been under-paying Ike while other promoters and managers were highly interested in Ike due to his promising boxing career. Managers and promoters don’t want boxers to negotiate deals; they want to be the ones to do all the negotiations so that their underhanded deals will not be known by any other than themselves.

“Because of these dealers and their methods, we had to leave Dallas Texas and moved to Arizona to seek refuge from them. Unfortunately, they followed us to this state and the nightmare continued. They tapped our phones, forced themselves inside our Gilbert home, they put chemicals in all of our food and drinks, and they will disengage our house alarm and enter our home at any time of the day of night. The Gilbert police have several records of our calls and reports concerning this matter. These promoters went so far as to fly and bring false charges against Ike in Gilbert and Scottsdale while he lived with me in the same house, by paying a couple of women to accuse him of attempted kidnapping and sexual assault. The police investigated these charges and threw them out because there was no basis for these charges against him. Since they did not achieve their aim here they followed him to Las Vegas and repeated the same charges, which has kept Ike in jail for six and half years,” Ike’s mother said in the letter.

She said her son was accused of being mentally unstable, forced to take medications and denied proper legal representation.

“Ike has never really been tried or convicted of these false accusations or charges, but nevertheless, he has lost six and half years of his young life. The Las Vegas court sent Ike to Reno mental hospital for evaluation, but before his arrival the staff had been informed that Ike was dangerous, crazy and many other suggestions that made the staff apprehensive to his arrival.

Upon Ike’s arrival at the hospital, the staff found that these statements were not even close to being truth rather they found Ike to be peaceable, respectful, loving and cooperative,” Mrs Ibeabuchi said.

“Drugging him out”

Ike’s mother said when the Las Vega court ordered the forced medication of her son; she confronted the physician a certain Dr Henson who was charged with the responsibility on why as a licensed physician he was administering the drugs on him when he was not insane. She said he merely replied that he was ordered by the court to do so.

“I asked him if that if the court asked him to kill would he kill as a licensed physician?” she said.

She was that the end of the day, her son was “intimidated, drugged out and with the effect of the drug dragged into the court to plead guilty by the Las Vegas public defender for alleged criminal offence he did not commit”.

“The judge knew about the drug Ike was given before court hearing because Ike told the judge that he was on forced medication and he can’t reason properly but the judge ignored him. Today, Ike, my son sits mercilessly in prison at the prime of his life, wasting! What did he do?” she lamented.

She provides the answer herself.

She said in December 1999 whilst Ibeabuchi was still under house arrest, Bob Arum, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Top Rank, the boxing promotions outfit, visited him to get him to sign a contract with Top Rank. She said both parties reached agreement but that Arum later altered the terms of the agreement reached between his company and Ibeabuchi agreed upon. Part of the agreement included featuring Ibeabuchi as an undercard in an upcoming Oscar De LaHoya fight in addition to Top Rank agreeing to commit between $150,000 to $175,000, to Ibeabuchi’s legal defence.

Mrs. Ibeabuchi opted out of the agreement and for that he “he was thrown back to jail the next day”.

“Since then different promoters and managers have promised to get him out if he agrees to sign contract with them. All these means that evil is behind this whole thing,” she said.

Arum, the Top Rank CEO accused of treachery by Ibeabuchi’s mother, has a different account of what transpired. In a 1999 interview with the Las Vegas Sun, Arum said Ibeabuchi made unrealistic financial demands.

“The kind of money he says he wants to fight is so far out of line that it’s completely unrealistic. On top of that, he wants a bonus and he didn’t seem to care what may happen if he doesn’t beat the criminal case,” Arum said.

He said he told Ibeabuchi what he could offer but the boxer didn’t seem to be on the same page with him.

“The way I look at it now, I’m not going to put good money after bad. I think I’ll cut my losses.”

Voice from a Nevada jail

With the deal with Arum falling through Ibeabuchi ran out of options and so became a convict after his sentencing two years later in 2001.

In jail, Ibeabuchi devoted his time to keeping his body and mind in shape. Believing he would be freed anytime as he continued to maintain his innocence, he trained hard and studied hard. In the course of time he was able to acquire three college associate degrees from Western Nevada Community College, in General Studies, Business, and Management. He also acquired a paralegal certificate via correspondence from Blackstone Career Institute in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

In 2007 Ibeabuchi’s conviction in Las Vegas was overturned by the Supreme Court of Nevada. Rather than effect his release, the lower courts in the state ignored the ruling even after the state’s Supreme Court re-affirmed its ruling.

Eight months before the Nevada Supreme Court ruling, Ibeabuchi had in an interview conducted with East Side Boxing, a boxing website inside the Nevada jail, insisted on his innocence.

“I would like the fans to know that I am an innocent man, and that I am being made a scapegoat for my perspicacity. Many know this. Nevertheless, I am dealing with this unfortunate circumstance to the very best of my ability. I have not stopped fighting and I never will. I was proclaimed the most dangerous man in the ring in 1999. Now with my academic achievements and life experiences, I feel I have the ability to take huge strides outside the ring as well,” he told the reporter.

From the interview, it is evident that Ibeabuchi has undergone some form of transformation. He had become spiritual than he was when he had gone in. He spoke of engaging in spiritual exercises like fasting and praying every morning for six hours in prison.

“My life, even in prison, depicts a life that has been lived in the bible many times. I like to see myself as the (Baptist or the Messiah with God 1st), like Daniel in the Lion’s Den, like Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace, but never burned, like Jacob who had run from his hairy brother in Dallas. Like Samson who saw wisdom and humility when his eyes were gone, like Moses who ruled scorpions and snakes in the desert, and I could go on and on,” he said in that interview.

Out, and in again

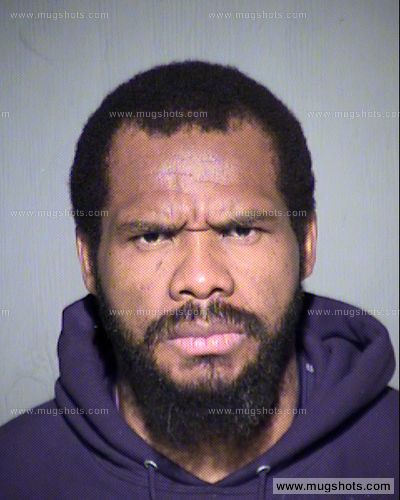

Ibeabuchi would eventually complete his term at the Nevada prison in early 2014 but he didn’t walk into society a free man. On February 28, 2014, he was moved to the Washoe County Jail on February 28, 2014, and was eventually transferred by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to the Eloy Detention Centre in Eloy, Arizona.

He was eventually released by the USCIS in November 2015. He was placed on lifetime probation. Sadly, for him, his mother who had spent her time fighting to secure his release, was not around to savour the moment. She had passed away in 2014.

Still believing he could re-enact his previous exploits in boxing, Ibeabuchi plotted a comeback. He reached out Mike Koncz, an adviser of Manny Pacquiao, in a bid to rekindle his career.

At 42, though he had kept shape in prison, boxing promoters did not fancy his chances of making any impact on the heavyweight division no matter how shorn of its former glory it had become.

During the period of exploring the possibility of a comeback, Ibeabuchi also turned his attention to regaining the millions of dollars in cash and investment he made during his brief five-year professional boxing career. To secure them, the funds were in his name and Kushner. His mother later got Ibeabuchi to sign over a Power of Attorney to a lawyer. This, he said in a telephone interview, was done to deny Kushner access to his money.

Out of prison Ike experienced difficulty claiming his money. The lawyer refused to relinquish control over the money and hand them over to Ike. He said the following the sale of the bank holding Ike’s money, the funds had been transferred to the buying bank, which refused to pay the interest he was entitled to and which he had received on a regular basis from the original bank.

The lawyer sued the new bank, and claimed he could not relinquish control of Ibeabuchi’s money until the case in court had been disposed off. Ike for his part sued the lawyer.

His effort to regain possession of his money was short-lived as he was re-arrested in April 2016 in Gilbert, Arizona, five months after he had been set free. He was deemed to have violated the terms of his probation.

Questions but no answers

One of the conditions of the probation Ibeabuchi was said to have violated was the requirement that he undergo treatment upon his release. It is not clear whether Ibeabuchi was aware of this requirement or whether he did not deem it necessary as he felt himself in top mental and physical condition upon his release from prison.

From interviews granted by Ibeabuchi to different reporters while in Nevada prison, he seemed normal enough.

Robert Frizel, Head Boxing Correspondent of realcombatmedia.com who interviewed Ibeabuchi a few times after his release in 2015 noted:

“Ike’s physical conditioning programme was geared only towards maintenance. Ike wanted to leave Arizona, with permission from the authorities monitoring his probationary status, to return to boxing training. His ability to leave Arizona remained unclear. Ike was apparently unaware of a requirement to begin a treatment program in Arizona related to his 1998 conviction in a sexual assault case.

“This needs to be clarified. Ike was convicted separately in 2001 of attempted sexual assault and battery in Las Vegas.

It now appears, based on this writer’s comprehensive research, and conversations with Ibeabuchi, that Ike was unaware of the treatment programme requirement tacked onto the previous conviction, and Ike apparently gotten nailed and jailed on the old warrant,”.

Today, Ibeabuchi is in an Arizona jail and will not be out until September 2019. Though his travails he has maintained he is innocent of the allegation that took him to jail. He feels cheated by the system.

In one of his interviews with Brizel in 2016 before he was re-arrested, he re-asserted his innocence of the crime which he was accused of in Las Vegas and which ultimately landed him a 20-year jail term.

Ibeabuchi told Brizel the only crime he committed was to solicit for a prostitute not attempted rape as he was accused of.

“Going back to the beginning of time, I am innocent! All I did was solicit prostitution. In Clark County Nevada, that is prosecuted. I confessed to NRS 201.354 prostitution, which is not allowed as a matter of law, and not what they claimed I did. The status allowed only what happened by matter of law. I called a call girl from The Mirage (Hotel and Casino). Wouldn’t go shy about confessing to what I did as a matter of law, versus the punishment Nevada gave me,” he told the reporter.

Ibeabuchi accused the prosecution of deliberately withholding information in their desire to have him nailed.

“Unbeknownst to me, she had pled guilty to prostitution in 2001. I would have won my case because the state would have lost its (star) witness in 2001 (my accuser). She had been convicted. The state did not reveal that information to me when I gave an Alford plea (I didn’t admit my guilt but I avoided going to trial). They were legally bound to do so (reveal all of the facts regarding their witness against me, which they knew) in constitutional practice to reveal any information in conflict to my case. If she was a prostitute when she testified in state court-[and she said she wasn’t a prostitute-[(then) she’s a liar (gave false testimony). I never testified. She was protected by immunity. In 2001, she was convicted of prostitution (previously, before she testified against me). I didn’t know about her prior convictions when I pled guilty in Nevada in November 2001,” Ibeabuchi said.

By 2019 when he’ll due for release, Ibeabuchi would be 47 years old; it would also be 20 years since he last stepped into the ring in a professional capacity. He would be too old to mount any meaningful challenge to the younger and fitter boxers of today.

Ibeabuchi’s story is a tragic one of a burgeoning fairy tale cut short by hubris. For generations to come, it will remain a cautionary tale of the limits of exuberance and a byword for missed opportunity.

IBEABUCHI STATS

Age: 46

Born: Isuochi, Nigeria

Nickname: The President

Category: Heavyweight

Stance: Orthodox

Height: 6ft 2in

Reach: 76in

Total fights: 20

Wins: 20

Wins by KO: 15

Losses: 0