Record melt uncovers Arctic landscapes trapped in ice for 40,000 years

For the first time in more than 40,000 years, blue skies and sunshine once more grace Arctic landscapes previously entombed under thick ice caps.

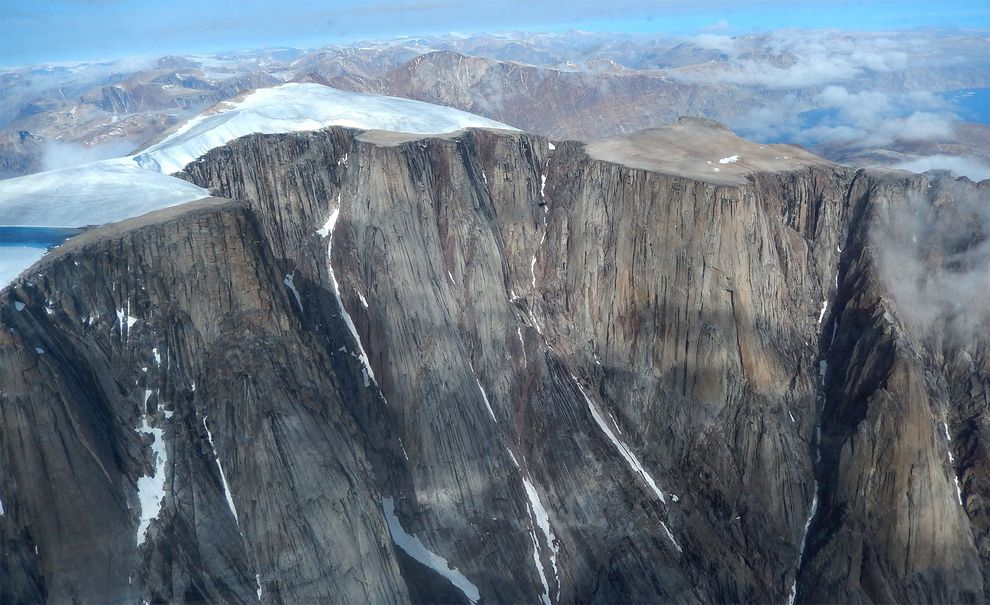

In a new study published in the journal Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Colorado’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), say the dramatic changes taking place on Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic stem from what’s likely its warmest century in the past 115,000 years.

“The high elevation landscapes that host these landscapes are striking in their own right, but knowing that the surface that you are walking on has been ice covered for millennia, and only now being exposed, is humbling,” lead study author Simon Pendleton told MNN. “In addition, knowing that the high degree of preservation holds much information about past ice cover history, and the prospect of the knowledge that can be gained from these landscapes is exciting.”

The most remarkable evidence of the underlying landscape’s last exposure to sunlight are the preserved remains of ancient mosses and lichens that Pendleton and his team scour for along the edges of the ice melt. Unlike glaciers, which slide along the bedrock and grind to a pulp almost anything beneath, ice caps remain stable for long periods of time. As such, anything caught beneath them ends up as part of a vast frozen time capsule.

“We travel to the retreating ice margins, sample newly exposed plants preserved on these ancient landscapes and carbon date the plants to get a sense of when the ice last advanced over that location,” Pendleton said in a statement. “Because dead plants are efficiently removed from the landscape, the radiocarbon age of rooted plants define the last time summers were as warm, on average, as those of the past century.”

Despite being entombed for tens of thousands of years, some of these mosses are fully capable of “waking up” and restarting photosynthesis.

“The strange thing about these mosses is that a lot of them can just start growing again,” Gifford Miller of the University of Colorado Boulder explained in a video. “They’re the closest thing to a zombie that I know of — the living dead. They haven’t done any photosynthesis, no hint of life in often many thousands of years and once they come out again and the ice melts back, if they haven’t been disturbed, they’ll start growing again.”

To paint a comprehensive picture of just how widespread and unprecedented the glacial retreat on Baffin Island is in modern times, the INSTAAR team collected 48 plant samples from the edges of 30 different ice caps at varying altitudes and exposures. After being analyzed, they found that all 30 sites had been completely covered by ice for at least the last 40,000 years and possibly longer.

It’s a shocking shift, Pendleton told MNN, that was easily observable during the study’s field campaigns from 2013 to 2015.

“Even over those few years, our return visits to ice caps showed that tens of meters of horizontal retreat was not uncommon,” he said. “The simultaneous exposure of preserved plants of varying ages also indicates the unprecedented nature of modern retreat.”

According to the research team, rapid warming of the Arctic over the last century has accelerated melt to the point that now all ice caps on Baffin — even those at the highest elevations — are receding.

“When viewed in context of temperature records from Greenland ice cores, these results suggest that the past century of warming is likely greater than any preceding century in the past 115,000 years,” they write.

They add that it’s possible the island, the fifth largest in the world, could be completely ice-free in only a few centuries.

“We hope to continue our work up on Baffin Island; as the ice caps and glaciers continue to retreat, they will continue to expose more and more of these ancient landscapes,” Pendleton said, “allowing us to continue to expand the records we have published here.”

Culled from Mother Nature Network(www.mnn.com