The Dehumanizing Logic of All the ‘Happy Ending’ Jokes

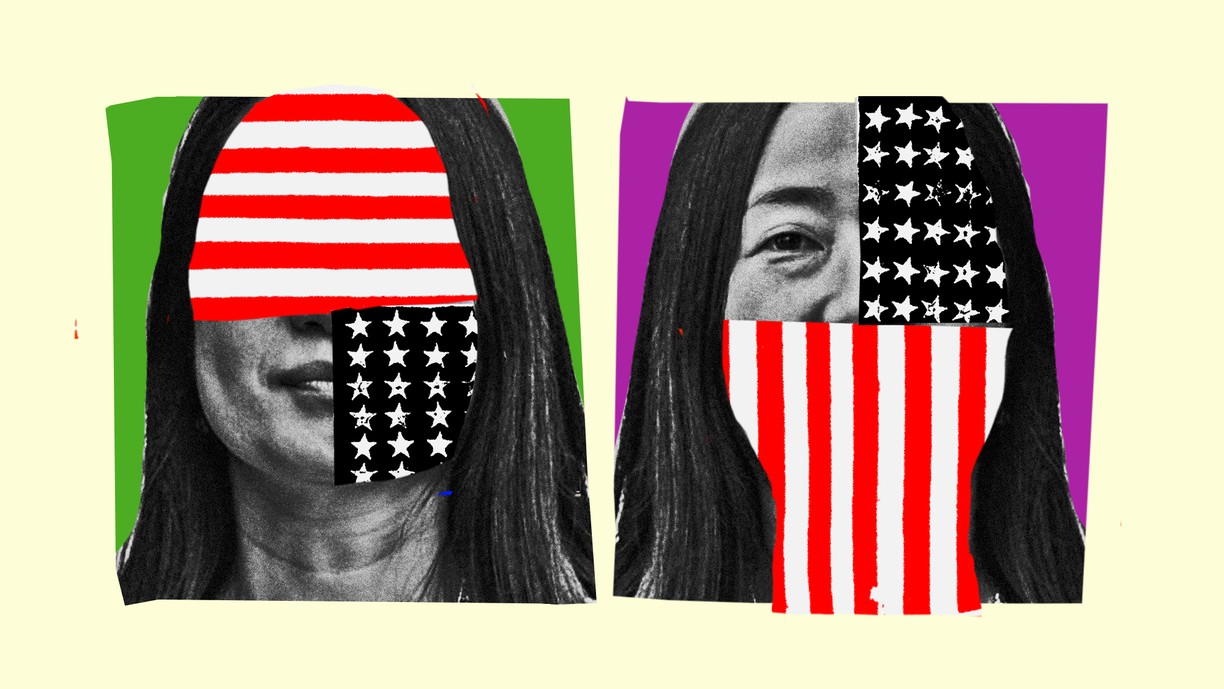

The Atlanta shootings speak to a prejudice that is deeply ingrained, if largely unacknowledged, in American society.

Almost a week has passed since the shootings at three massage parlors in the Atlanta area, which resulted in the death of eight people, six of them Asian or Asian American women. The Atlanta police have yet to say that the incidents were motivated by racism, seemingly in part because the shooting suspect told them that he suffers from a “sex addiction.”

Yet almost immediately after the news broke late Tuesday night, a certain kind of response started popping up on Twitter: “No happy ending then?” “‘Youngs Asian’ massage parlour … they love you long time.” Social-media comments are notorious for their unthoughtfulness, but these brutal jokes speak to a prejudice that is deeply ingrained, if largely unacknowledged, in American society. The shootings took place within an escalating pattern of anti-Asian violence, but they are also part of the longer history of gendered violence in the United States. They cast light on the continued degradation of Asian women, the criminalization of women connected to sex work (or imagined to be), and American male fantasies of entitlement to Asian female bodies.

This entitlement is both quotidian and dangerous. For many women of color, the idea that misogyny and racism often go hand in hand is a fact of life. Almost every woman of Asian descent I know who grew up in America has experienced some version of strange men cooing at her, “Me love you a long time,” or has endured the unctuous hailings of ni hao ma and konichiwa or the intrusive come-ons that mix flattery with a vague sense of threat. As a young woman on the receiving end of such unwanted attention, I never said anything about it, because I suspected that most people would consider such incidents minor inconveniences, even though these kinds of encounters always produced a sickening sensation in the pit of my stomach.

Then Atlanta happened, and that old pit grew into a persistent pain. Watching law enforcement relay the explanation of the 21-year-old white man who admitted to the murderous rampage—he told police that he shot the women to try to eradicate “temptation”—was an exercise in both disbelief and recognition. It was a harsh reminder that these acts were a very real, very lethal manifestation of what goes unspoken behind all those seemingly harmless, supposedly flattering solicitations that dog Asian women: a profound disregard for them as people, an aggressive imputation of their imagined availability, and a deep assumption of racial and masculine prerogative.

As a woman of middle-class privilege, I have been mostly sheltered from the harsher forms of this aggression, but it is a grave mistake not to understand that “mild” and “violent” racist sexism are on the same continuum. Here’s the thing that many people find hard to accept: Hatred does not preclude desire. Hatred legitimizes the violent expression of desire.

Let us be clear: By his own admission, the shooting suspect could not control his desires, so he went out to eradicate the objects of his desires. Is there a more stark articulation of the deadly intent of racist misogyny?

Racism and sexism are partners that stoke each other with frightening ease. Racism may be caused by many factors—demagoguery, religious intolerance, economic resentment, inherited bigotry—but its expression is almost always about the assertion of power. And whenever vengeful male power is in play, it is never good news for women. Anti-Asian racism and long-standing Western colonial attitudes about the plunderable “Orient” enable the possessive denigration and dehumanization of Asian women; patriarchy and sexism further fortify such presumptions.

Since the first big wave of Asian immigration to the U.S., in the 1850s, Asians have suffered discrimination and violence. Few know, for example, that the lynching, burning, and killing of Chinese residents were commonplace occurences up and down the West Coast during the 19th century. Since then, the perceived threat of the Yellow Peril has never really gone away; instead, it has circulated throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, easily revived during times of war, economic downturn, and disease.

The Atlanta shooting also reminds us that America has long conflated Asian female sexuality and criminality. The first time that Chinese litigants appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1875, the case involved the perception of Chinese women as prostitutes. Sensationally known then as the “Case of the 22 Lewd Chinese Women,” it centered on a group of young women who were denied entry into the U.S. at the Port of San Francisco despite having proper travel documentation, because the immigration inspector thought they were prostitutes based on how they looked to him. The state of California argued that it had the right to protect itself from “pestilential immorality.” The Supreme Court eventually ruled in favor of the women, not necessarily because the Court thought they were innocent, but because it wanted to reaffirm the federal government’s authority to regulate immigration.

That same year, the U.S. passed the Page Act, which was introduced by Representative Horace F. Page of California to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” Apparently, to California officials, Chinese women equaled prostitutes. The Page Act was the first restrictive federal immigration law in the U.S., effectively prohibiting the entry of Chinese women into the U.S and foreshadowing the more stringent Chinese Exclusion Act. This in turn created the mostly male “bachelor societies” of American Chinatowns, placing the few Asian women who were here in even more physical, social, and economic jeopardy. In the 20th century, U.S. foreign policy and military presence in Asia extended this old racial-sexual imagination to the figures of the so-called “comfort women,” the “war bride,” and the sex worker.

That the murdered women in Atlanta worked in massage parlors—spaces that are deeply racialized and sexualized in the American and global consciousness—only underscores the continued invisibility and precarity of immigrants and service-industry workers. The victims included Xiaojie Tan, who was days away from her 50th birthday, and is survived by her husband and a daughter who recently graduated from college. Yong Ae Yue, 63, was a working mother too. Hyun Jung Grant, 51, was a single mother working overtime to raise two sons. These were workers, mothers, wives—women who lost their life to one person’s desires and, we have to acknowledge, to a larger culture of racialized misogyny.